“Since Benjamin Franklin’s kite-flying days, thunder and lightning have not grown less frequent, powerful, or loud – but they have grown less worrisome. This is exactly how I feel about my irrationality now.”

As mentioned in the previous article, we are descendants of those hunter-gathers with quick thinking and fast reactions, and thus, it is tempting for us to make decisions based on immediate instincts rather than careful contemplation. Our thinking process is prone to error, naturally. Besides, due to imperfect information, it is almost impossible and certainly unnecessary to avoid all thinking errors and live a perfectly rational life. Having said that, the fact that thinking errors are inevitable should not discourage us from knowing more about them. Although familiarising ourselves with various examples of thinking errors may not prevent us from falling into those traps, we can at least know what traps we have fallen into, and probably, gain some skills to get out of the trouble. Knowing those errors is not an effective vaccination, but who knows, it might be a helpful pill --- at worst, a placebo.

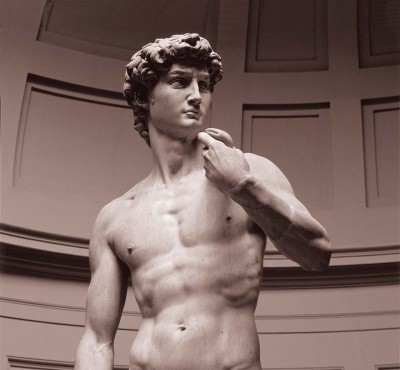

Most thinking errors have rather standard names, such as ‘XXX bias’, ‘fallacy of XXX’, ‘XXX illusion’, but it may be not suitable to take the literal meaning of the words sometimes. Thus, it is crucial to understand thinking errors not only from their names, but also with relevant examples and explanations. Without further ado, let’s start to talk about ‘something that is not David’!

(I) Confirmation Bias

“The confirmation bias is the mother of all misconceptions. It is the tendency to interpret new information so that it becomes compatible with our existing theories, beliefs and convictions. In other words, we filter out any new information that contradicts our existing views (‘disconfirming evidence’).”

No one can be free from the confirmation bias; it is so common and powerful that the author calls it ‘the mother of all misconceptions’. By simply examining our own life, we could find plenty of evidence: when we pursue our dreams, we tend to underestimate or even ignore the obstacles along the way; as we strengthen our religious or political beliefs, we are always able to doubt any doubts that are against our faith; while we are falling in love with someone, we feel that he/she is the right and perfect one in every possible aspect.

One interesting thing about the confirmation bias is that most of the time, even though we know we are falling into its trap, we just don’t care. Firstly, every one of us craves for a sense of security deep in our hearts, so we do not wish our fundamental beliefs to be challenged or changed. Even when we are exposed to evidence against our existing beliefs, we choose to regard them as distractions and temptations. Take a personal example. After making my mind to join the church, I have encountered many rational arguments against the existence of God and realised the role of confirmation bias in influencing my attitude. Still, I have never thought of living without my confirmation bias regarding this issue – I cannot prove it, but I choose to live it. In fact, it is my conviction that every person ought to have some faith beyond all doubts (which means your faith cannot be doubted by anything) to lean on, be it religious, philosophical, political or whatever you like. It is undeniable that we have been born into a world full of uncertainties, so why not make something certain for us to go through all these uncertainties? Secondly, it is impractical to live without the confirmation bias. Our past experience and belief do not only exist in our mind, but also influence it by shaping our perspectives. In other words, how we perceive and analyse new evidence is inevitably affected by what we already believe and know. Clearly, before I learned about the concept of the confirmation bias, I did not notice as many examples of confirmation bias as I do now.

Even though it is impossible and unnecessary to avoid the confirmation bias all the time, we need to refrain ourselves from falling for it in certain circumstances when critical analysis and objective judgments are essential in decision-making. One way to do it is suggested in the book at the end of Chapter 8:

“Literary critic Arthur Quiller-Couch had a memorable motto: ‘Murder your darlings.’ This was his advice to writers who struggled with cutting cherished but redundant sentences. Quiller-Couch’s appeal is not just for hesitant hacks, but for all of us who suffer from the deafening silence of assent. To fight against the confirmation bias, try writing down our beliefs… and set our to find disconfirming evidence. Axeing beliefs that feel like old friends is hard work, but imperative.”

(II) Illusion of Control

“The illusion of control is the tendency to believe that we can influence over which we have absolutely no sway. This was discovered in 1965 by two researchers, Jenkins and Ward. Their experiment was simple, consisting of just two switches and a light. The men were able to adjust when the switches connected to the light and when not. Even when the light flashed on and off at random, subjects were still convinced that they could influence it by flicking the switches.”

After reading this paragraph, you may laugh at the innocence of the men in this experiment – how could they be deceived by such a simple trick? Yet, every one of us can fall into a similar trap. Imagine the following scenario: You want to buy a lottery ticket, but have no time to go. After deciding to ask your friend to buy the lottery ticket for you, will you give him a series of numbers or tell him to randomly pick the numbers? Anyone who chooses the first option has an illusion of control in this case. In fact, it does not really matter whether we choose the numbers ourselves or not.

Why do we tend to overestimate our level of control then? My answer is that the illusion of control can give us the confidence and courage to make firm decisions and move forward. If we succeed, we become more convinced that we have the power and control over our own destiny; even if we fail, we usually attribute the result to other factors instead of clearly pointing out the illusion of control.

Interestingly, we are often taught to form and strengthen our illusion of control, not otherwise. Remember all the chicken soup stories and inspirational talks told to us by teachers and parents? Remember the famous adage ‘Where there is a will, there is a way.’ we have recited and quoted since primary school? It seems that believing in this adage is as innocent as believing that you can influence the randomly flashed lights by switching on and off. However, there is a difference: the men in the ‘switch experiment’ will never have the opportunity to really have a control of the lights, but people who have a will may be more motivated and thus, able to find the way. Despite all the successful cases, ‘Where there is a will, there is a way’ is still an illusion -- a beautiful one -- which gives us the hope and power to achieve. It is heartening to feel that we are the masters of ourselves, but it is also important to know that we are not. I am grateful for all the chicken soup and fairy tales I have heard and learned, yet I tell myself: having a strong will does not guarantee a desirable way; at best, it increases the successful rate.

In the Chapter 17, the author introduced many examples of the illusion of control in our daily life, from the control buttons of many traffic lights to the ‘door-open’ and ‘door-close’ buttons in elevators (in fact, I feel shocked to read that many of them are ‘placebo buttons’), from the gesticulating of football fans in front of the TV to the monetary policy implemented by the government. In fact, the illusion of control, despite of being considered as an error, often play a positive role in many aspects. Yet, you still need to be careful about it – never force yourself to control anything that is out of your control. Let’s remember this piece of advice:

“Focus on the few things that you can really influence. For everything else: que sera, sera.” (Whatever will be, will be.)