Last night I was asked to share with the investigator how I came to know that The Book of Mormon is true, a typical question which I have been asked hundreds of times. Indeed, my answer could be summarised into one sentence: I know The Book of Mormon is true because I know some parts of it are true. To borrow an analogy from one of the sister missionaries, it would be: You do not have to taste the whole chocolate bar before knowing that it is delicious.

Any rational being, be him a disciple or an atheist, can logically doubt my answer from at least two aspects. Firstly, are you sufficiently justified when claiming to know that some parts of the scripture are true? Secondly, suppose that you do know that some parts of the scripture are true, are you justified to conclude that the whole book is true by induction?

As a person who has chosen to believe in God for over five years and learned epistemology (i.e. a study on nature and construction of knowledge) for two years, I am not really troubled by the first doubt. To explain it briefly, the degree of certainty and justification required for a claim to be qualified as knowledge differs for each individual discipline. Hundred-percent reasoning and perfect rigour are required for a mathematical conjecture to be qualified as true knowledge, but for science, a branch of subjects closely related to the real world and uniquely characterised by falsifiability, reasoning in vacuum cannot give us any scientific knowledge at all, so we cannot expect pure reasoning and absolute certainty behind any scientific theory. Whereas to obtain religious knowledge, one needs reasoning, experience, and much faith, for faith is the leap over the gap of reasoning. Hence, in order for me to know some parts of the scriptures are true, faith besides reasoning plays a very important role. In fact, I would say that faith and reasoning work hand-in-hand in constructing and justifying religious knowledge, at least for me. It would have been impossible for a person with no religious background to have faith if nothing made sense to her.

The second doubt is something which came into my mind and puzzled me during our discussion last night. As I thought more about induction during these two days, I raised several questions to myself and tried to give an answer to each of those. Clearly, there is much more to discuss about induction and my answers here are far from being perfect. Yet, I would like to give a humble account of these questions and answers in the hope of invoking ideas which are more rigorous and enlightening.

Question 1: What are the similarities and obvious differences among mathematical induction, scientific induction, and religious induction?

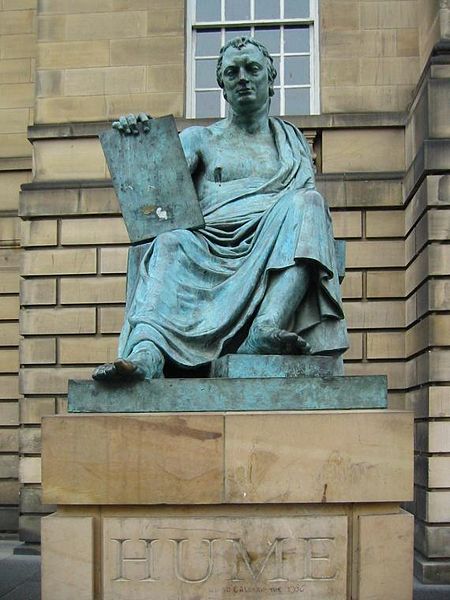

Question 2: Why is the “problem of induction” proposed by David Hume a concern in science, but not a problem in mathematics? ( i.e. why is mathematical induction a deductive process?)

Question 3: Is the induction in religious sense affected by “the problem of induction”? If yes, what does it have in common with scientific induction? If not, what does it share with mathematical induction?

Question 4: To summarise, what makes a “generalisation” process immune from the “problem of induction”?

Question 5: If a “generalisation” process is immune from the “problem of induction” proposed by David Hume, does it mean that it is free from all epistemological problems? (i.e. do we have other reasons to doubt it?)